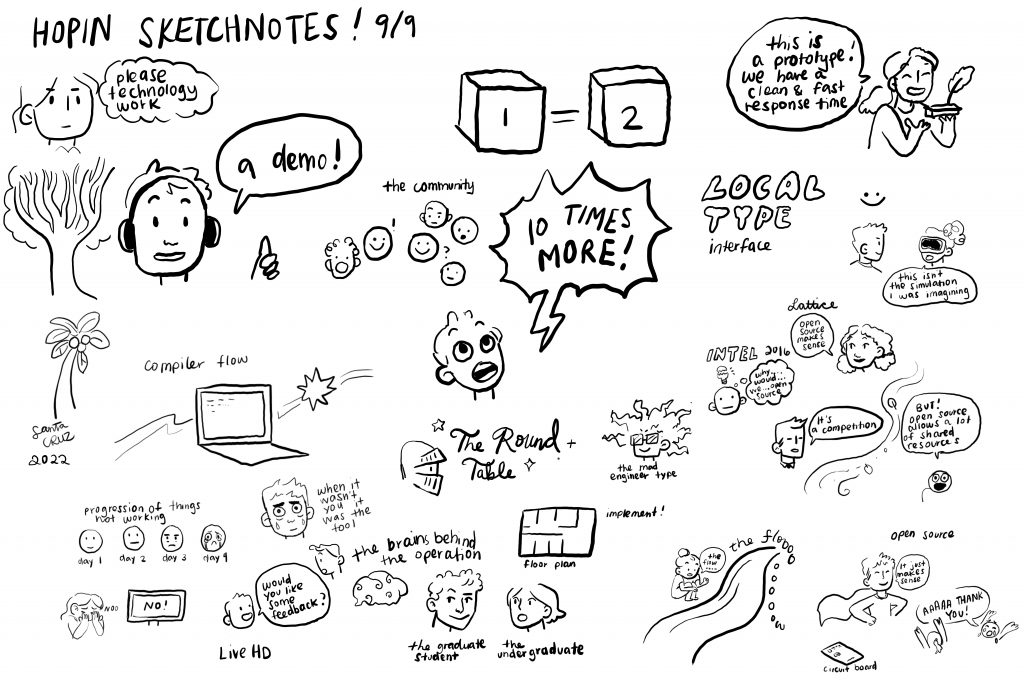

Red Hat Research Days 2020 was an experiment in recreating face to face interaction between researchers, Red Hat engineers, customers and partners in the virtual space. The goal; moving research into open source communities. And the event was immensely successful — there’s more collaboration on projects. Part of this success can be attributed to the ease by which some of the technical concepts and ideas were well conveyed through appealing illustrations during the event.

To learn more about this exciting multi-faceted field with diverse job prospects, Red Hat Research spoke with Andrew Federman, Máirín “Mo” Duffy and Madeline Peck about their experiences as digital illustrators.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Red Hat Research:

How did you all get into the field of illustration?

Madeline:

Well I got into illustration because I liked making up stories and drawing in general and so when someone told me that there was an entire field for that, I thought, “Well, that’s what I’m going to do.”

Andrew:

I would say it was accidental. I was working in filmmaking and through a friend I started working at a company where we would capture conversations on white boards live and people knew I could draw so they said, “Andrew, go ahead, jump up there”, and I’m like, “No way, I can’t do that. I don’t want to be in front of the room. I’m not a performer.” And so I was just capturing words at first and then started adding pictures. With whiteboards there’s a crutch, which is kind of nice because you can erase and start all over. Over time, the need for real time artifacts has also grown. It’s one of those things where you look back and all of a sudden you’re in your 40’s and you didn’t notice any change day by day but over the course of time, there’s actually been a significant change.

Mo:

I started very young. My dad bought me a set of Prismacolors when I was six years old. My parents were always giving me art supplies and I used them to do all sorts of things. My dream was to be a Disney animator. But by the time I got to high school, they were not doing as much animation here: most of it had been shipped overseas and they only had a team of 5 people in Orlando. So then I was going to be a video game artist – I grew up learning how to play text parser adventure games, so they were a big part of my childhood. I could do the graphics for that and thought it would be fun. But by the time I was graduating high school looking at college, a lot of those companies sort of folded or got bought out. So it wasn’t really the thing it was when I envisioned myself doing it.

So I’ve always had that since I was young. I was always drawing and creating projects and even doing them on the computer. From the start I had something like Smurfs Paint and Play on a Coleco ADAM…if anybody has heard of that.

Andrew:

Wow, that’s amazing.

Mo:

Yeah, so I was drawing with Smurfs and they had these digital stickers but you could also draw and we had it hooked up to the TV because that’s what you did then.

Andrew:

When you say draw, what was the interface back then?

Mo:

For the Coleco the main interface was this big joystick.

Andrew:

Wow, that’s amazing.

Mo:

Yeah, and when the Wacoms first came out I didn’t get one for a really long time. I don’t think I got a Wacom until I was in college. In high school, I had this Disney animation suite that was actually really a nice program, but this was only either EGA or VGA, but I was doing digital onion skinning with it and stuff like that. I’m just a nerd for this stuff.

Andrew:

Wow, that’s really cool. That ColecoVision thing’s kind of blowing my mind.

Red Hat Research:

You really do know your craft, which is great. How would you describe your illustration style? And if you still haven’t found your style, what are you aspiring to get at?

Madeline:

I watched shows like Adventure Time and Cartoon Network shows and they’re very noodly. That’s how I’d describe them. And so when teachers are pushing realism and learning how to draw from observation, I think that’s a skill that you need to translate that into a style in the future and I think it’s a good base but it’s not the end all be all. And so after that I was going full noodle, full round comforting – if this character was a cartoon mushroom you’d want to hug it or turn it into a plush type of thing. And one day I’ll find a way to make a red hat character plush, I swear.

Andrew:

Yeah, that’s a great question and depending on what kind of artist you are, it can be an easy question or a hard one. What I do for work is very different from my personal artistic style, which is typically very abstract and I use a lot of paint and markers on paper. But speaking of just my illustration style, my visual notes have really been pushed by the speed at which I need to work. So the imagery that I use has gotten simpler and simpler.

If I’m doing any imagery along with the text it needs to be as simple and graphic as possible so I can get something that I like that’s interesting and pulls your eye in but it also can be drawn in a few seconds. So it’s been pared down over the years, I used to put a lot more detail into things and now I try to draw things with as few lines as possible.

Mo:

I grew up being a Disney wannabe so I kind of trained myself doing the Disney style. And I started from there and I got into comic books for a while so I like comic book styles too. My style is all over the place, but when I’m doing stuff like sketch noting, it’s really more about the function than the form. So just like Andrew said, it’s like the bare minimum you need to express the idea. Because for me, with sketch noting it’s more I want to broadcast the concept and not necessarily produce a nice illustration. So the style could be whatever’s quick and dirty, basically, but shows the concept. It’s a very functional form of illustration.It’s like drawing in pen almost, even though you can erase when you’re sketch-noting, in most cases, I just don’t.

Andrew:

I’ve been doing this for almost two decades on mostly foam board with actual markers and when I first was doing it, sometimes I would sketch stuff out in pencil because I was afraid to commit to something right away, but I realized there’s just no time for that when you’re doing a live content capture, so it forced me to just go for it. And every time I’m doing it I’m like, “I wish I’d put that word three inches to the left because I’m running out of space”, well I just have to deal with it. So you’re constantly forced to deal with the decisions you’ve made in the moment that aren’t necessarily great decisions but you have limited amounts of information. If someone’s speaking, you don’t know if what they’re going to be saying in 30 seconds is more important than what you’re capturing now, but you have to make a certain call like, “Okay, I’m going to make this in big letters because it sounds important.” And then 30 seconds later they say something even more important, so do you draw that in even larger letters or maybe in a different style? So it’s very different than when I’m doing my own art when I have all the time in the world and I can sketch stuff out and do versions and layers. It’s almost like a different part of my brain.

Mo:

It’s a very different process because it’s linear whereas when you’re doing a planned piece you almost start like an image loading in stages. Like you try to get the rough of the full and plan everything out and then put in details and then another layer of details. With sketch-noting it’s just like, “Go”, and there’s no revisiting it, there’s no planning.

Red Hat Research:

Since adapting to the situation is key, what would you say is the strangest thing you’ve ever illustrated? Something that you drew and a few seconds later thought, “why did I draw that?”, but of course you had to go along with it.

Mo:

The weirdest thing I probably ever illustrated that everybody knows about is the SELinux coloring book. Dan Walsh came into my cube and he’s like, “I want you to draw pictures of cats and dogs so I can explain SELinux.”

And I’m like…, “Cats and dogs? SELinux??”

And it’s actually a very good metaphor but you get to this point where you’re doing this type enforcement feature of SELinux. And we had to convey that you’re enforcing that dogs are not allowed to eat cat food. But it’s not just like the dog can’t eat the cat food, you have to actively enforce it. So to illustrate ‘actively enforcing not allowing a cat to eat dog food’, I had Tux the Linux Penguin (because this is done through the Kernel Module) putting a dog leash on the dog and pulling the leash to stop the dog from eating the cat food. And it was very strange and I felt kind of bad too but it’s like he’s not abusing the dog, he’s just pulling the dog from the cat food. But how else would you illustrate that? It was just bizarre.The drawing style was terrible but it was quick and it was dirty and it was done.

Madeline:

I guess I drew a portrait of Weird Al next to a poodle dog and I really accentuated their features to look the same, and that was the weirdest thing I’ve ever drawn. Only because Weird Al is already weird and when you accentuate him…

Andrew:

That’s awesome. Nothing major comes to mind; but there’s all kinds of new things that come up in meetings, and oftentimes I don’t really understand what people are talking about because I’m not a technical expert, but I do visual notes across all industries. So sometimes people will say things like, “key escrow”, and, “fuzzing C extensions”, and so I have to basically come up with a super literal depiction of some of these things that don’t have anything to do with what they’re actually talking about, but people seem to really like that and they feel like it draws a connection between the jargon and a lay understanding of the concept. And that’s all I’m left with sometimes, because I can’t stop a presenter in the middle and say, “What are you talking about?”

Mo:

Once I did an illustration (I understood what the discussion was about but I was trying to be funny) where there’s this thing in Linux called PXE boot which helps you to provision a system remotely and put the operating system on it over the network. In my visual notes, I had a little pixie flying around and I called it the pixie boot. And this pixie boot would swing a boot on computers and that would deploy the software. People really liked it even though it was nothing to do with what PXE booting is.

Red Hat Research:

Nice. So what software and hardware do you use for illustration? I’m asking this for someone who’s interested in getting started in the field but doesn’t know where to start just because there’s a ton of technology to use out there already.

Mo:

I’m very opinionated about it. I only use open source software, I only ever have used open source software. Right now on my daily driver is a ThinkPad Yoga that has a built in Wacom digitizer, so the entire screen is a Wacom tablet. It’s like a Wacom Cintiq built into the laptop. It has a stylus and everything so I can draw on it. And for sketch noting, like the sketch noting we did for research days, I used Krita. Krita.org is where you can download it, it’s a beautiful cross platform drawing program that’s focused on digital painting. When I do other things, depending on what I’m trying to do, like the coloring book stuff I did with vectors so I used Inkscape, which is kind of like Illustrator but open source. Yeah, so in the past I’ve used other tools like MyPaint, but I jumped over to Krita because the development was a lot more active and a lot more community support for it. And always do it with Fedora as the OS.

Andrew:

I have a question about the tablet you’re using. Is it a Wacom tablet? Or is it like one?

Mo:

My laptop has a Wacom tablet built in, It also has a built in pen and then you can just draw on the screen. I’ve been using ThinkPads with Wacom built in them for a few years now. I started with the X30, T30, and then I had an X220, I think I had another one in there and then the Yoga. So I’ve been using these for like ten years at this point. ThinkPad has always had Wacom integrated laptops for at least the past ten years and I’m a big fan so I’ve always gotten them.

Andrew:

I should look into that. So the technical stuff is all pretty new to me, I was basically just doing things analog until this year. I would draw on large pieces of paper or foam board and then at the very end of the process there was a digital component, but it almost had an analog feel. I would take a photograph and just clean it up in Photoshop, so that was the final image. This year I’ve had to scramble and learn a bunch of new things. And I didn’t want to invest any money in new equipment initially so I’ve been using an iPad that I had been using to basically watch movies. I’ve been trying all kinds of stuff, and right now I’ve settled into Affinity Designer and Adobe Fresco but I’m trying to find something that covers all the bases and nothing really does, so it’s still an experiment. And honestly, drawing on glass with a little pen where no matter what tool you’re choosing, the actual thing in your hand is always the same, hasn’t been the most satisfying for me coming from markers on paper where I can see if my marker has a wide tip and can feel exactly how wide that tip is when I’m drawing, whereas now I have to retrain my brain.

Mo:

Yeah, that’s the difference between using a Wacom versus an iPad with a nubby. Because when you use the Wacoms the pens have integrated tilt and pressure detection so you push harder and the line is thicker, you tilt the pen a little bit different it changes the angle of the line.

Andrew:

I have an old Wacom tablet; not the ones where you’re drawing right on the screen. It’s a separate tablet where it’s just black, and the iPad pencil is pretty good. It’s got pressure sensitivity and tilt. Does the Wacom have a roughness to the surface so it creates some resistance?

Mo:

It depends. The ThinkPad one is sort of like however your screen is, and this one, the Yoga, it’s got a little bit of grit to it. It’s not completely glass smooth, but if you go with something like the Cintiq models you can actually switch out the tips.The Cintiq is like the gold standard but for various reasons I’d rather not use one.

Andrew:

Why is that? Is it because of the software?

Mo:

I used to travel so I couldn’t bring it with me and the one I used it was massive; it was like 24 inches, it was very heavy. It had this big thick cable coming out of it, so it was just very hard to be comfortable maneuvering it. I think Cintiq has a mini one now, but with my laptop it’s lighter and it’s just easier. It sucks because you can’t get the extra pens for the laptop based ones, they’ve locked them to specific hardware so you have to buy a Cintiq to be able to use them.

Andrew:

Yeah, I’m curious about trying out a Cintiq…

Madeline:

I got a tablet that would hook into the computer when I finally knew that I was going to art school and I was applying and I was like, “it’s an investment.” And that’s what I used for the sketch notes things and I also used Krita and I use Inkscape for Fedora. But then I did invest in an iPad pro because I wanted to do more digital art traveling-wise. And it’s good for what it is, I can make finished pieces.

Andrew:

What do you feel like the limitations of the iPad are?

Madeline:

Well I use Procreate so I really like how you can pay one time and just use it. But I think just making bigger files or projects, that would be a limitation. If I want a large canvas in DPI they’re like, “No you can only have one at a time.”

Andrew:

What about the screen size?

Madeline:

I got the 11 inches one, I think, because I wanted it for traveling. But now I have friends who have the bigger one since they’re using it all the time. I guess it makes sense. Sometimes I wish it was bigger but then I just go onto the tablet. There’s definitely pros and cons to both.

Andrew:

Yeah, I have the bigger one and it still feels very small compared to what you’re able to do with the Cintiq type tablets. How big is your laptop screen?

Mo:

Resolution-wise it’s just a hair under 4K. But in terms of actual size, I think it’s like 22, maybe 21.

Andrew:

That sounds really nice. So open source drawing programs, I know nothing about this. But if I wanted to start looking into this, where would I go?

Mo:

I have an article that I do every few years discussing the top creative tools for open source. I do a rundown of everything, like all the drawing programs, photo manipulation, video editing, post processing, all that stuff. It has links to all the places you can download them and stuff like that.

Red Hat Research:

Thanks Mo. That’s really useful. Andrew you mentioned that in most cases when you’re illustrating you usually don’t have domain expertise. In your experience what has been the most challenging topic to illustrate?

Andrew:

Well, I did some really heavy aviation engineering stuff once and it was too technical for me, I couldn’t understand the physics. This group was mostly talking about lift and drag and displaying formulas and I was really trying to find something to hold onto that I could draw in real time, so that was really challenging.

Also, sometimes there’s a disconnect between what people think I’m there to do and what I’m able to do. Once, I was drawing for a government agency and they came up to me while I was drawing and said, “Hey, Andrew, we were hoping you could do just pictures with no words.” And the thing is, illustration is almost always a companion to some text. So illustration can be very, very abstracted and mysterious because it’s got the anchor of the text that’s next to it. But when you’re doing visual notes, at the end, the visual note is typically all that’s left of the talk or the conversation. So if it’s just images, it’s very hard for it to stand alone, especially if people are trying to convey complex topics.

Mo:

Well, a lot of times surprisingly people still don’t know what being a ‘UX designer’ means so they hear the word design and they just think art and creative. So I get asked to do so many things. The number one request is, Can you make us a logo for our projects?” Or, “Can you make us a t-shirt design?” So I do them, I’d rather not, but I’ll do it. It helps somebody out and sometimes it helps me get into that project. So that’s an example of someone asking me to do something that maybe isn’t what I’m looking to do. In terms of somebody trying to make me do something that I’m not really able to do, usually it’s, “Hey Mo, that’s a great design you came up with. Now code it.” I mean, I could. I’m probably not the best person to do it though because it would probably take me two months whereas it would take somebody that knew what they were doing a week. So that’s the other confusion that happens sometimes.

Andrew:

What do you think people have in mind when they hear UX designer

Mo:

It’s sort of a really interdisciplinary field, so it really depends on what their previous experience was with it. You can come to UX from computer science, you can come to it from marketing, you can come to it from psychology. It’s so intersectional that it really depends on their experience. But a lot of times people hear UX design, they don’t even hear the UX part and then they just assume it’s graphic design.

Andrew:

Right. So all they think about is the colors and the shapes of what they’re seeing.

Red Hat Research

That’s interesting. So how would has the virtual work impacted illustration?

Madeline:

Well, there are a lot of freelance illustrators and a lot of design and illustration work that was done virtually and so maybe you didn’t actually have to go into an office. Even when the pandemic hit, it was still possible to get your work done as an illustrator. But now it’s several months later and I think working with people face to face really brings your art to life and so I think it will be a balance of, in the future. I think it’s great to talk to people face to face every now and then to remember why you’re doing it and to remember where it’s going to go and who it’s going to be seen by.

At my school, we have studios so I really got into the mindset of going into the studio and having that ambient proximity of people around you just silently working or being able to ask them for an opinion, I enjoyed it. I also enjoyed work at my own desk, but when it couldn’t happen I was bummed but it wasn’t the worst thing because safety first.

Mo:

Everything you can do in this field you can do from a home office. But where I feel like, especially over time, I’m missing stuff is just inspiration from going out and attending cultural events or going to a museum. I think that your brain needs brain food from a variety of places to be able to design well. You can’t just stick in your lane and just not go outside of it. I think cross-pollination across different disciplines and fields and everything is just fantastic fodder for great design, and it’s hard to get that when you can’t really leave your house.

I think the best way to understand an advanced technical topic that I need to illustrate or design is to just sit in front of a whiteboard with an engineer and just have the engineer draw stuff and then talk me through the concept and I ask questions. And they draw on the whiteboard and we work it out together. It’s the best way to understand tech that you might not understand and it’s really hard to do that over video chat.

Andrew:

I think it’s just echoing what you both have said – what I miss the most is everything you get from being in proximity to others. Even if you’re not necessarily directly interacting with them all the time, there’s transmissions that happen. If someone’s working nearby and you can see what they’re doing, it has an effect on you and it makes you, I don’t know, you’re getting something and they may be getting something from you. I think it’s the isolation that’s the hardest and there’s also a sameness to it.

And this might just be my own problem. Just not being that used to the medium yet; no matter what style I draw in, no matter what application I’m using, at least right now, it’s always that same glass surface and that same pen. That’s really hard to wrap my brain around because in the physical world there’s all kinds of different brushes and markers and I might be drawing on a board that’s three feet wide and then I might be doing something on an eight foot wide board, and those are the largest pieces of foam core that we would use, if I’m just going to talk about the visual notes.

I’m replacing some of that with virtual versions for the time being until it’s safe to be around other people again. Madeline you said something about ambient proximity, I could really relate to that, seeing other people working, maybe on something completely different, but nearby and just that radiant inspiration is something I’m really craving.

Red Hat Research:

There’s been a lot of focus on STEM subjects in the past and we now see a push for STEAM (science, technology, engineering, art and math) education too. I’m curious what all of you think about this new proposal.

Mo:

I think the scientific method, the engineering process and the basic design process are the same exact thing with different words. So whether or not the ‘A’ is there or not, you’re doing it. It’s nice to give the discipline the recognition of being in the acronym, but whether or not it’s there, kids will be doing it. And honestly, I think that with a lot of these things, emphasizing art and emphasizing design makes the end product better, it makes it more human. You could implement some technology but if nobody can figure out how to use it because it’s so badly designed, it’s as if you never implemented it at all because if you can’t use it what’s the good of having it? When we work in tandem it becomes stronger.

Andrew:

It’s the first I’ve heard of that, adding the A, but it makes a lot of sense to me. I don’t know the way STEM is taught now, but I know the way that I was taught art, there was a lot of emphasis on process and not necessarily always what do you come up with in the end, and I feel like there’s a lot of value in that not just for art but for all kinds of different fields. It’s like this built in failure and experimentation that is essential to actually getting somewhere interesting. It goes absolutely without saying, and you see it sometimes with young artists, and I have one child that’s really into art, and they get really upset when the finished thing is not what they had in mind, sometimes they go right for the end right from the beginning, they’re doing the final drawing. And I’m like, “You know, why don’t you play around with it? Fall on your face, mess up.” I feel like if that were integrated throughout, if that’s what the A could bring to STEM, I think it would add a lot of value.

Mo:

I think there’s also a big emphasis with STEM stuff on money, like, “Are you going to get a job at the end?” And that’s why some people are reluctant to add the ‘A’, which I think is absolutely insane, because again, how are people going to use the thing if you haven’t thought about the art side of it, if you haven’t thought about the design side of it?