Red Hat Research Quarterly

From silos to startups: why universities must be part of industry’s AI growth

Article featured in

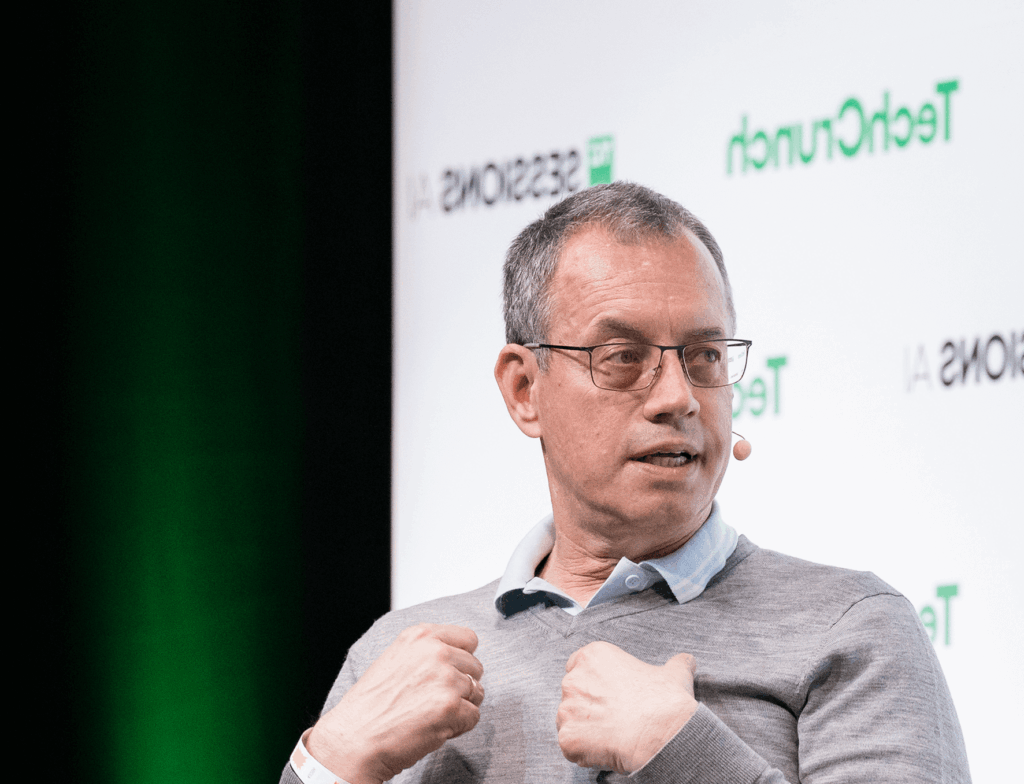

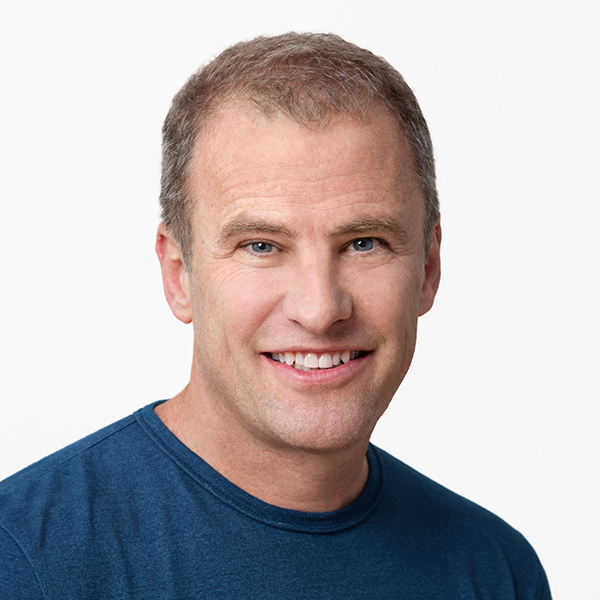

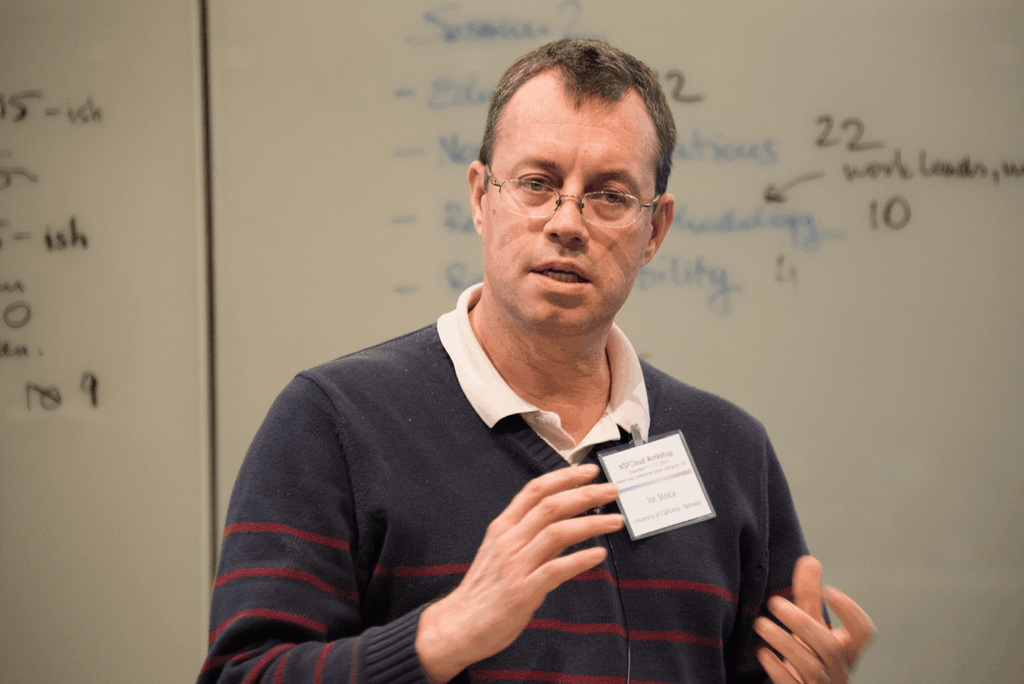

At the May 2025 Red Hat Summit, Senior Vice President and AI CTO Brian Stevens helped announce the launch of llm-d, an open source project aimed at meeting the need for distributed GenAI inference at scale. As readers may know, Brian had most recently been the CEO of Red Hat’s January 2025 acquisition Neural Magic, the leading commercial contributor to vLLM. The llm-d project amplifies the power of vLLM, already the de facto open source inference server, and among the founding supporters of the project is the Sky Computing Lab at the University of California, Berkeley, where vLLM was first developed under Sky Lab director Ion Stoica. Ion is also known for his work on Ray, Apache Spark, and Apache Mesos, among others, and he’s the co-founder of Anyscale, Databricks, and Conviva.

What’s weird? Until we asked Brian to interview Ion for RHRQ, the two had never met. Ion has been instrumental in UC Berkeley’s highly successful model for university-industry relationships—a topic of keen interest for Red Hat Research, which has been perfecting its own model for productive academic partnerships for several years. The research team also helped enable Red Hat’s llm-d development on the Mass Open Cloud, a Red Hat-supported hub for industry, higher ed, and government collaboration on research and development. Clearly this was a conversation we needed to host. Brian and Ion discuss the road to AI, the dangers of siloed AI development, the case for enabling universities to engage in AI research, and what they’re excited to see next on the horizon.

—Shaun Strohmer, Ed.

Brian Stevens: What first attracted you to computer science and technology as a field of study?

Ion Stoica: I was born in Romania during communism. Like many in my generation, I was pretty good at math and sciences, participating in Olympiads and such. So it was natural, when thinking about college, that physics was one choice, and the other was the equivalent of computer science back then. Personal computers were growing in popularity, and it seemed like an exciting new world was starting to evolve where you could touch more people, so I picked computer science. When I came to the US to do a PhD, it was at the time of the rise of the internet, so I got my PhD in networking. I finished the PhD in 2000, in spring of 2001 I joined the faculty at UC Berkeley, and I’ve been here since then.

Brian Stevens: When I started in computer science as an undergrad in 1981, I didn’t know it could be a real career. I had been exposed to it a little bit, but I never would have thought it would become the center of so many things we do, or the center of so many great companies. Many decades later, I’m still in awe. Were you thinking about career options back then?

Ion Stoica: When I started my career, it was still during communism, so I didn’t think about it in that sense. But it was clear things were developing; even in Romania back then there were some state companies building their own version of PCs.

Brian Stevens: Are you surprised looking back? Now it seems obvious that computers are the center point for everything, but I’m still amazed I picked so wisely.

Ion Stoica: There was so much growing excitement, for example with microprocessors, the first personal computers— I remember I had a Commodore 64—and so forth. Everywhere you looked it was expanding, so it did seem limitless.

Brian Stevens: Yet now some big tech companies are cutting back on hiring new developers and focusing on using more AI. It’s not unlike how our work was focused on operating systems and infrastructure and storage— all the stuff I know you’re passionate about—and then the internet came, and then cloud, and a lot of businesses weren’t doing infrastructure anymore.

Embracing new technologies

Ion Stoica: Maybe that’s why I’m in academia. I’m always very excited to embrace the new trends. I did my PhD in networking—actually I started working with operating systems but then the internet took off so I started focusing on the internet and networking. But internet infrastructure quickly matured, which made it harder to have an impact in networking. So I started to focus on peer-to-peer networks for a few years, but then it turned out the problems we sought to solve as a community were not as big as we thought. There was an assumption that you couldn’t, for example, scale up content delivery without peer-to-peer networks, that when you have movies and all of these big objects you want to distribute over the internet, the backbone will not be able to support it. Peer-to-peer was the solution to this problem: avoid the congested backbone and send the data across the nodes at the edges instead. Don’t go through the downtown, right? Use the back roads. However, it turned out that the internet infrastructure was able to scale fast enough to support these new workloads, and this made peer-to-peer less relevant for solving this problem.

See how we’re solving the next big problem: learn about co-design at Red Hat Research.

Then the next big thing was big data. I was jumping on that bandwagon very early—at Berkeley we were early doing work with big data and with the cloud. A few years after I came to Berkeley as junior faculty, we had a lab for studying reliable distributed computing, called RADlab, where we were building our own clusters. We were collaborating closely with industry, and we had a meeting with James Hinton from AWS around 2006. He told us, “Hey, we are going to have these new services, so instead of building clusters yourself, why don’t you try them?” So that was S3 (Simple Storage Service) and then EC2 (Elastic Cloud Compute). So because of that we were early adopters of the cloud. It was also because of collaboration with industry that we got into big data. We were working closely with Google and then with Yahoo, which was developing Hadoop for storing and processing large data sets. So we started to contribute to Hadoop, and then we developed Apache Spark for large-scale data analytics.

And then I moved to AI and systems as the need to scale these systems was growing. I’ve been happy to jump from one to another—so you can say that I’ve been quite an opportunist in my career!

Brian Stevens: And yet they’re not really new choices or even pivots. It’s all connected, from the networking background into distributed systems and so on.

Ion Stoica: One leads to another: you’re using data, so now you are going to focus more on the AI side of data, how you process the data, how you evaluate your data, and things like that. Like you say, they are all related. For example, distributed computing has become much more relevant because you can barely run a useful workload on a single machine now. Networking is also super relevant because it is now the bottleneck for running these workloads distributedly. It all connects.

An open source world

Brian Stevens: Back in my DEC (Digital Equipment Corporation) days, I was lucky because we had access to BSD (Berkeley Software Distribution, aka Berkeley Unix), and it felt like an open source world. I was contributing to code largely written by others, and I felt like I saw a glimpse of open source even though I didn’t know what I was looking at. I didn’t think about it that way; it was just the only world I knew.

Imagine what your world would have been like if open source had not been a factor. And it was not just a toy; it was actually powering the first incarnations of clouds.

Ion Stoica: It was interesting to see the power of open source early on in my academic life. I remember the first operating system conference I attended in 1995, I believe, and there was this panel asking if operating system research was dead. Microsoft had an iron grip on the operating systems market, right? Then you have all of these companies taking Unix and trying to provide their own flavor, like SCO (Santa Cruz Operation) from Santa Cruz, AIX (Advanced Interactive eXecutive) from IBM, Ultrix from DEC, and of course SunOS from Sun. It was very balkanized on the Unix side, still mostly proprietary versions of Unix in one way or another, except maybe Unix BSD, and then you have Microsoft.

So what was academia going to do? People were saying there was no hope for academia or research to play an important role in operating systems any longer. But then a few years later you have Linux and the open source movement, which we were lucky to contribute to. That was fantastic.

Brian Stevens: It’s definitely set up for a better world. Things commoditize faster, but the barriers aren’t there. Think of what people can build and create now.

Ion Stoica: Shifting the conversation, though, I’m disappointed this doesn’t happen as much as I would wish in open source in AI today.

Brian Stevens: True—why do you think that is?

Ion Stoica: If you take a step back for a moment and make an abstraction about why this happened, things are clearly very different from other instances of innovation. For instance, think about the evolution of the internet. The internet was really a result of open source and a result of industry, government, and academia working closely together.

But with AI, what we are seeing today is the opposite. All these leading AI companies like the frontier labs are very siloed, and each of them is doing similar things. When you are talking about developing models and model architecture, academia is not really in the game because of the huge resource requirements. And there is not a lot of collaboration between academia and industry. There is very little flow of information between frontier labs and academia, unlike how it was during the development of the internet, so there is little diffusion of innovation. Today, in AI, diffusion of innovation mostly happens by people moving from one company to another or starting new companies.

When academia is not at a disadvantage, it can not only contribute but power the innovation.

Sometimes people say “But all the innovation is coming from these labs anyway, so academia can just focus on something else.” When I hear this, I remind people that the main reason academia doesn’t contribute as much to these innovations is the lack of resources and the way the industry is structured today. When academia is not at a disadvantage it can not only contribute but power the innovation. Take LLM inference for example: not only do the the most popular open source inference engines come from academia, but also a lot of techniques, like flash attention, paged attention, and so forth.

The problem with silos is they slow down progress. Progress is driven by people, data, and infrastructure. Just thinking about people, the most efficient way to leverage your human experts’ efforts is for them to collaborate, to share the information. They can build on each other instead of just reinventing. The only way I know to enable them to collaborate is to have shared artifacts, and a shared software artifact is open source. And of course you need some shared infrastructure. You can see this is happening at a more rapid pace in the open source community in other countries than it is in the US today. Things are moving so fast that any time we lose, we’ll have consequences.

From research to startup

Brian Stevens: We just really met in the past couple of months but I’ve always known you because I follow this space, and your work and your companies. I know I want to sit back at the end of my career and feel I had something to do with something that changed the industry for the better. Would you say having your hand in some of these great companies and great technologies is a side effect of the research work you do, or is having a long term impact a goal for you?

Ion Stoica: Definitely. I’ve always been driven by the hope of making an impact. Dave Patterson has a great definition of impact: broadly speaking, impact means changing the way some people are doing their work for the better. That could extend to how they live their lives in general. The reason to take these projects to the next level, sometimes as a business, is to try to maximize their impact.

For instance, we started Databricks when more and more companies started to adopt it. That raised the question of what would happen when the students working on it graduated. Could people still depend on it? Early on, before we started the company, we tried to find a company to donate the project to, without success. That’s why we started Databricks, the company, to sustain the growth of Apache Spark and give confidence to companies and organizations they can depend on it. It was the same thing with Anyscale. Starting companies from university research is not the goal, it is a means to the goal, which is to maximize the impact of the research.

Brian Stevens: So you connect research to impact. I grew up, career-wise, at DEC, and I would spend a lot of time in our research labs, but they weren’t connected with a goal. It always felt to me, as a product person, that for them it was the research and research alone—it didn’t really matter whether or not their software lived on and made an impact outside the lab. I always said I wanted to be oriented towards research but connected towards driving an outcome after the research is done. And you’ve done that. I think a lot of research groups don’t.

Ion Stoica: I think if we can build real systems, we can use them as a platform for research. I’m always telling my students, “Everyone here is good at solving problems—that’s why you are here. You did well at school, and how did you do that? By solving problems to get high scores on tests and exams.” So one of the most important things to think about now is what problems you are going to work on. If you have a system that is going to be used by people, that will help you to find new problems you can work on. It always happens. When people are using systems, they find gaps or they use them in ways you didn’t expect, and they find problems. Now, if they find problems on your systems, it puts you in a pretty good position to solve them, because you are among the first to understand these problems.

Real users and real use cases for research projects push the technology and create new problems. If you can build the kind of systems used by people, it creates a compounded return on the research side.

You could go to different companies and find problems to work on instead. But why do you go to these companies? Because they have real users and real use cases that push their technology, and this creates new problems. So for me, if you can build the kind of systems that real people can use, it creates a compounded return on the research side. I find this very satisfying. Don’t get me wrong, of course it’s satisfying to build something used by many people. No question about it. But it can be even more satisfying finding new problems to drive your research.

Brian Stevens: I can bring that back to vLLM, which you guys founded at Sky Lab, and to the paged attention implementation. vLLM was the first algorithm to make LLMs run efficiently, and then wow, now there are all these algorithms building on it.

Ion Stoica: Yes, it’s exactly that. There are so many interesting problems to work on, we don’t have enough students to work on all of them. Also, I want to make the point that we do not build new systems just for the sake of it. We never start by building a new system to solve a problem we are interested in. We always start with existing solutions and try to figure out whether they can be adapted to solve that problem. Only if we think there are fundamental limitations with these systems do we build a new system.

Before Spark we tried to improve Hadoop to better support interactive jobs and machine-learning workloads. Before vLLM, we implemented PagedAttention in TGI (Text Generation Inference) from Hugging Face. When you do it that way, you start to see the gaps in the existing systems, and this is very important because you can narrow your focus about what the new system should do. In some cases, you can put your techniques in the existing systems—that’s fantastic.

But in many cases, when you try to improve the existing systems, you hit a wall. And you’re more likely to hit a wall in fast-growing areas, because it’s very hard to build a system that is good at everything and to anticipate future needs. Needs are sometimes going to evolve in a direction you didn’t expect. The existing systems were great for what the initial requirements were, but the requirements move fast and they can no longer satisfy these new requirements. But it’s good for students to have experience with the existing systems to understand the limitations firsthand and say,“Okay, what are the gaps?”

Even when we are building our own systems, sometimes unexpected requirements force us to rearchitect these systems. This was the story behind vLLM v1, a thorough redesigning of vLLM to better support new scheduling and parallelism techniques. The requirements are evolving because the workloads are evolving. At the same time, the hardware is evolving. And all these evolutions open new gaps between the hardware and the workload requirements. In the end, bridging these gaps leads to reinventing the existing systems or the emergence of new ones.

Brian Stevens: You obviously navigate the corporate-university relationships really well. People want to be attached to the brand, whether that’s you or UC Berkeley. What do you think has made those relationships successful?

Ion Stoica: I think at Berkeley one of the things we were lucky to have, more than maybe other universities, was this open source culture, coming from systems like Unix BSD and Ingress, the first open source relational database. And not just with software but with hardware as well, for example, RISC-V, the first open source instruction set computer. Berkeley also has these five-year labs, which were started by Dave Patterson, Randy Katz, and others. Each lab has a few faculty members and a few tens of students, all working together on the same mission for five years. The original RISC and RAID (Redundant Array of Inexpensive Disks) were developed in such labs. And this was something unique we inherited.

So you can create these labs, which are like an academic version of a startup. Before a lab starts, students and faculty will discuss the next things they are excited about and then start talking to industry, doing presentations of their ideas. It’s like a startup giving a pitch, but it’s not only a one-time pitch, it’s iterative. You get feedback and then you present again to various companies, and eventually some of these companies become your sponsors. So on the faculty side we discuss and gel around certain ideas, and we refine these ideas based on the feedback from our prospective sponsors. This process not only improves our ideas, but also gives sponsors some intellectual ownership even before the lab starts. Bringing that together is not easy, and it probably requires people to share the same culture. And then you need to reinvent even the most successful labs every five years—the brand of the lab goes away and you need to start from scratch.

I think that’s helped us build bigger things, because there are quite a few people working on the same problems for five years. The system is also nimble. As problems shift, the interests shift, and the next lab can have different people. It used to be that starting every five years was a good time period to keep up with changing technologies, but I’m not sure now. Maybe five years is too long, as the technology is evolving faster and faster. That said, another reason for the five-year period is that it maps well with how long it typically takes a student to graduate. We will see how these labs evolve in the future.

The future

Brian Stevens: We’re near the end of our time, so let me ask you what you’re keeping an eye on for the future. You’ve moved through all of these technology transitions—big data, cloud, AI—so what looks interesting to you next?

Ion Stoica: From my perspective, there are two things. On the system side, it’s about vertical integration, or co-design, across different layers, all the way from optimizing kernels for different accelerators and GPUs to agentic systems. Huge costs and performance requirements make co-design necessary, and we know from the previous era of high-performance computing that the best way to optimize performance and reduce cost is co-designing across different layers of the stack.

In particular, I think there will be a lot of innovation at the interface between networking and compute, finer grain synchronization, parallelism, overlapping communication with computation, and so forth. That’s one direction in which we are going to see a lot more activity. Many frontier labs are doing that themselves, but I think we are going to see a lot more of it in the open source community.

The second thing is building reliable AI systems. When I say reliability, I’m not talking about failures, I’m talking about reliability of results. That’s another big area of research. Right now the most successful applications, like code assistants and customer support, have a human in the loop who ultimately validates the answers proposed by these AI systems. To go to the next level and have things that may be autonomous or solve problems for which humans do not know the answers, reliability is going to be very important.

Brian Stevens: 100% agree.

Ion Stoica: Okay, now you answer your own question!

Brian Stevens: So you’ve seen my enthusiasm around distributed inference, and part of that was discovery around the question of how it could possibly be that you could increase the tokens more than linearly by going distributed, while also meeting the SLOs. But the part I worry about a lot, and where I think there is an opportunity, is that we’re building a collection of algorithms, tools, and methodologies, but applying them is semi-manual. You can configure for sizes of models, QPS rates, the latencies you want, the types of infrastructure you have, but how do you autoconfig? How do you build AI intelligence inside the system so it knows, varying over the course of days or weeks or whatever, how to apply these techniques?

We would have been wrong to build in all that automation in the beginning, because you need to observe and learn. But I think that’s a big opportunity, to create the AI orchestrator living inside of these AI systems that can, in the simplest terms, deliver the required SLO at the most efficient token production. That’s very hard to do at this point, and it just needs to be easier.

Ion Stoica: That sounds great.

Brian Stevens: Thank you so much for your time, Ion.

Co-design at Red Hat Research

Hardware-software integrated design, or co-design, has been an area of inquiry at Red Hat Research almost since it began, including work on FPGAs, reconfigurable hardware, and the Linux unikernel. The demands of AI workloads make this kind of exploration even more important, as Ion Stoica suggests. One area we’re currently focused on is quantifying the performance gap in factors such as throughput and training time between similarly setup Linux bare metal and Red Hat OpenShift environments for machine learning workloads. Our test case is training a GPT-2 class model from scratch.

At ASPLOS 2025 (the ACM International Conference on Architectural Support for Programming Languages and Operating Systems), our peers at IBM Research presented a paper on Vela, a virtualized LLM training system. The paper shows that it is possible to exploit the full performance of modern hardware for model training with commodity ethernet and OpenShift. We are in the midst of reproducing this work in the Mass Open Cloud using the 48-node Lenovo infrastructure with 4×400 Gbps NICs and 4 H100 GPUs on each node.

Our current focus is on experiments contrasting networking performance and training time for two 8-node clusters, where one is deployed with a standard Linux kernel on each node and experiments run as applications running across that cluster and the other is deployed using OpenShift with the applications run in pods. The work is not complete, but we think we’re finding that OpenShift, when properly tuned, can approximate bare metal performance, which would give us the capability to provide a distributed infrastructure that is much easier to share and manage for the owners while still providing excellent performance characteristics for people who want to work with and optimize models.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More like this

Ask Gen AI to design a CIO action figure, and you might get a guy in a dark suit with a briefcase and laptop as accessories. That won’t give you an accurate idea of Boston University CIO Chris Sedore, who’s held the post at Syracuse University, University of Texas at Austin, and Tufts University. You […]

The name Luke Hinds is well known in the open source security community. During his time as Distinguished Engineer and Security Engineering Lead for the Office of the CTO Red Hat, he acted as a security advisor to multiple open source organizations, worked with MIT Lincoln Laboratory to build Keylime, and created Sigstore, a wildly […]

“How many lives am I impacting?” That’s the question that set Akash Srivastava, Founding Manager of the Red Hat AI Innovation Team, on a path to developing the end-to-end open source LLM customization project known as InstructLab. A principal investigator (PI) at the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab since 2019, Akash has a long professional history […]

John Goodhue has perspective. He was there at the birth of the internet and the development of the BBN Butterfly supercomputer, and now he’s a leader in one of the toughest challenges of the current age of technology—sustainable computing. Comparisons abound: one report says carbon emissions from cloud computing equal or exceed emissions from all […]

What if there were an open source web-based computing platform that not only accelerates the time it takes to share and analyze life-saving radiological data, but also allows for collaborative and novel research on this data, all hosted on a public cloud to democratize access? In 2018, Red Hat and Boston Children’s Hospital announced a […]

Everyone has an opinion on misinformation and AI these days, but few are as qualified to share it as computer vision expert and technology ethicist Walter Scheirer. Scheirer is the Dennis O. Doughty Collegiate Associate Professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty affiliate of Notre Dame’s Technology […]

What is the role of the technologist when building the future? According to Boston University professor Jonathan Appavoo, “We must enable flight, not create bonds!” Professor Appavoo began his career as a Research Staff Member at IBM before returning to academia and winning the National Science Foundation’s CAREER award, the most prestigious NSF award for […]

Don’t tell engineering professor Miroslav Bureš that software testing can’t be exciting. As the System Testing IntelLigent Lab (STILL) lead at Czech Technical University in Prague (CTU), Bureš’s work bridges the gap between abstract mathematics and mission-critical healthcare and defense systems. His research focuses on system testing and test automation methods to give people new […]