Red Hat Research Quarterly

Opening the doors of tech: why diversity is critical to the future of computing

Red Hat Research Quarterly

Opening the doors of tech: why diversity is critical to the future of computing

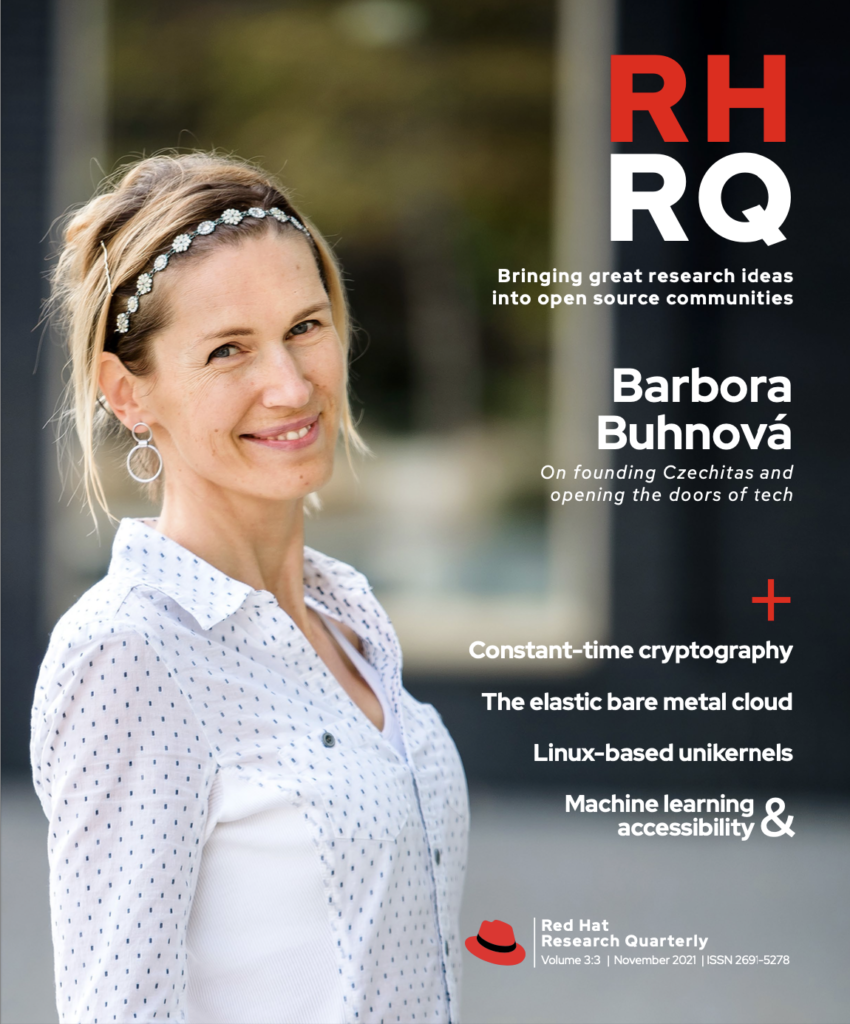

Red Hat Research University Program Manager Matej Hrušovský interviewed Barbora Buhnová, Associate Professor and Vice Dean for industrial partners at Masaryk University, Faculty of Informatics in Brno, Czech Republic. She is also the chair of the Association of Industrial Partners of Masaryk University, Faculty of Informatics, and is a co-founding and governing board member of […]

Article featured in

Red Hat Research University Program Manager Matej Hrušovský interviewed Barbora Buhnová, Associate Professor and Vice Dean for industrial partners at Masaryk University, Faculty of Informatics in Brno, Czech Republic. She is also the chair of the Association of Industrial Partners of Masaryk University, Faculty of Informatics, and is a co-founding and governing board member of Czechitas, a nonprofit organization aimed at making IT skills more accessible to youth and to women of any age.

Matej Hrušovský: When did you start getting interested in the issue of women’s participation in computer science, and when did you start taking action?

Barbora Buhnová: Founding Czechitas, the nonprofit organization we are running in the Czech Republic, changed my perspective on women in tech in a big way. Many believe that girls are not really interested in computing, and that’s why there are so few women represented in computing. But with Czechitas, we see a different picture. When we introduced coding classes for girls, they became so successful that within one day of opening a new course for 30 women, we could get 350 registered.

It was a complete mind shift for many of us, recognizing that girls are extremely interested in learning coding and getting into the IT world. They were just waiting for a different kind of invitation, which we were able to offer.

Matej Hrušovský: What was the spark for the idea to start Czechitas in the first place?

Barbora Buhnová: We have heard many girls say that they find coding interesting, but they believe that it is too late to start. That is a theme we’ve seen quite a lot: “It’s too late for me. I was never encouraged to try it when I was younger, and now I am twenty and it’s too late.” So that was the spark—let’s give it a try. Let’s just spend one day with hands-on coding, and you can find out for yourself if you have this passion and want to work on it.

“In the end we want to become more open, because we need more people in tech. We need boys, we need girls, we need everybody who is interested…”

Our first course was on Ruby On Rails, within the international Rails Girls initiative. But after that course, many participants were really excited about continuing. So the people who were engaged in organizing the course and teaching the course decided to create the continuation.

We did some introductory coding, some web development, things like mobile development. We did Android development very early—maybe too early because for somebody who has no coding experience, starting with Android development was very ambitious—but it was a lot of fun. There’s a spirit of exploring something that might be too difficult, but being in it together.

Matej Hrušovský: Where do you see Czechitas going in the future?

Barbora Buhnová: We have different pillars in which we are trying to achieve certain goals. One of those is popularization: changing the belief that IT is only for a very limited group of highly intelligent people. We steer away so many talented people who choose different disciplines because they believe that IT is too difficult for them.

The second direction is transitioning into tech: changing a career or changing a study direction. For example, a young woman studying economics could change her direction to tech, because she already has a skillset we need. There is no reason for her not to choose it, except her own beliefs about the industry and her chances to succeed.

This also applies in terms of career change. In the Czech Republic, we are known for having very long maternity leave. The average is six years, since many women have a second child while they are on leave with the first. That is six years of staying home with zero connection to a career. What we see is that these women often reconsider their career direction. They are thinking about using this time to learn something new and then starting a brand new career. That is a huge opportunity, but at the same time it is very difficult for them.

Matej Hrušovský: Why do you think there is this barrier for women in society at all?

Barbora Buhnová: It is a combination of factors, and it is different in different countries. I am now Vice Chair of the European Network for Gender Balance in Informatics (EUGAIN), which represents thirty-eight European countries. One of the things we do is try to understand these differences among countries. For instance, how do these issues differ based on the structure of the society, such as countries in which multiple generations of a family live together.

In the Czech Republic, we ran a study with 150 participants trying to compare the directions and perspectives of two personas: a woman who is in tech, and a woman who wants to learn tech now that she is an adult. For the second persona, we were asking, why isn’t she in tech in the first place?

We identified a leaky pipeline here in the Czech Republic. It starts with a lack of encouragement when they are little girls. That’s something the participants all referred to. They say, “It never crossed my mind because I’ve never been encouraged to even think about it.” Access to encouragement is a very subtle change that may make a huge difference.

The second interesting factor is that many girls are multidisciplinary. They like languages, and they like history, and they like biology, and they like computing. They like math and they like arts. Given that wide range of interests, if you get a really bad teacher in computing, you just forget about that direction and focus on the other directions you find interesting. A really good teacher is a critical influence. That can be a challenge when some teachers are not excited about technology themselves.

Families can also be an influence. Some girls we spoke to were interested in computing, but their family was discouraging them and directing them towards a career where it was easier for the family to imagine they would succeed. Their mom might say, “Maybe you would be happier as a nurse,” in an attempt to protect her from going into this unknown world where she cannot imagine a successful, happy place for her little girl.

So it’s not about bad intentions; it’s just the stereotypes parents have of computing as a world where their girls might not thrive. For that reason, it’s crucial for Czechitas to work on popularization with adult women, because they will be those mothers and role models for their little daughters. The way they talk to their daughters about computing is crucial.

These elements build on each other. When a girl gets over these hurdles and finds herself at high school or university studying computer science, she wants a sense of belonging. In the Czech Republic, we know that the ratio of girls to boys in computing is very low, so the opportunity to identify with others who are successful in that field is hard to find. And many girls in that stage then start mimicking the majority group and forgetting about their own talents and strengths.

Matej Hrušovský: It’s a fear of standing out, right?

Barbora Buhnová: Yes. And in that case, they’re also trying to be good at what they see the boys are good at. They diminish their own potential by trying to mimic someone else. That hurts their confidence, because they will never be able to mimic someone else’s strengths as well as they can use their own. Different people have different perspectives and will see what another person misses. Girls need to understand that it is valuable to have their unique talents that they can bring to the table and really stand out. That is the true power of diversity.

I’m now talking about myself a bit. For a big part of my early career, I was really trying to be a great specialist. But I will never beat specialists at being a specialist when I’m not a specialist myself. I’m a generalist. I’m a multidisciplinary mindset person. I need to see the big picture. And of course I used to struggle with my confidence, because nobody gave me a role model with that same mindset.

That’s a sad thing in some academic communities: until you prove yourself to be a good-enough specialist, you won’t be respected as a good generalist. Schools expect little kids to show that they love spending the whole day on a small coding assignment and debugging it. If they don’t love it, they are told they are not a good fit for computing. That’s the message they hear from the teachers. But is it really a competency we need? Is computing only for those who want to spend all day debugging their assignment?

And by opening up the field in this way, it becomes attractive for more boys as well. Diversity is not about boys and girls. It’s not about women and men. Diversity is about being able to see value in different mindsets and problem-solving strategies, and seeing value in people who are different—without first testing to see if they are just like we are. It means being able to see those other qualities, even if, at the moment, they are not as good as we are at this or that specific task.

In the end we want to become more open, because we need more people in tech. We need boys, we need girls, we need everybody who is interested, and we don’t want to give anybody the feeling that they are not good enough just because they are different from the people who are in tech right now.

“Maybe twenty years ago, academia and industry could function as two separate worlds, but not anymore. We must work together.”

Matej Hrušovský: We haven’t yet talked about your role as the Vice Dean for Industrial Relations at the Faculty of Informatics. What changed for you when you became Vice Dean?

Barbora Buhnová: As I mentioned already, I’m a generalist, an integrator. That’s the talent I’m bringing to any kind of project, including my engagement here at the university. So this is about integrating industry and academia by building bridges. That’s something we still need to learn, because often in computer science we are all specialists in our own thing, like we just talked about.

Otherwise, we miss the value of integrating people who have different priorities and knowledge and expertise. The ability to put that together to create something more feels very exciting to me. So what changed with my role is that I got more support to be very open and to bring more industrial representation to education at the university level. Also, we are trying to establish study programs that take the best of both worlds to help raise our students as future experts who have knowledge from both angles, academia as well as industry.

Matej Hrušovský: What are the challenges of putting those two things together?

Barbora Buhnová: The main challenge is that we are all too busy to think about it. People are too busy to start something new. But industry is not the same as it was ten or twenty years ago. Maybe twenty years ago, academia and industry could function as two separate worlds, but not anymore. We must work together. Each one of us needs to make the investment to build the connections, have the painful conversations, and find ways we can work together effectively before this will be fruitful and have visible benefits.

There still can be research teams that will need their encapsulated space in academia—that depends highly on the research problems we have. But academic evaluations are changing, suggesting that having universities co-creating together with industry will be the way to excellence. There is no way to excellence while staying isolated from industry completely. The exceptions are very very few. That is painful for many to talk about, but it is true.

You can find many people at universities who believe that they know better, so why should they talk to industry? And there are many people in industry who believe they know better, so why should they talk to universities? Some ability to be humble and listen to what the other side has more expertise in is the first step, and we are still not very good at it.

Matej Hrušovský: Have you been able to bring your interest in diversity to your role at the university?

Barbora Buhnová: Yes! Here at the university, the management of the faculty is really supportive of cooperation with Czechitas and supporting girls in their interest in tech. At the same time, however, there is some pushback from students who do not want anybody to get benefits that they are not able to get themselves. And now there is some pushback from students who see this as a way to disadvantage the male population.

We need to help people understand that we are trying to generate interest from all the talent reservoirs we have in the Czech Republic that might study computing. Studies from other countries are showing that activity to raise girls’ interest in computing has beneficial effects on boys as well. So many boys have self-selected away from computing, possibly because they don’t consider themselves specialists in technology. Now they see these activities for girls and think, “Okay, maybe I can also reconsider computing.” The effect is beneficial on both sides.

Matej Hrušovský: Have you seen any significant increase in how many women come to study computer science or work at IT companies?

Barbora Buhnová: We are monitoring the numbers, so we can see the progress. There are some peaks, some up and down. When I was starting to study, there were roughly around five percent women in my class. Now it’s roughly twenty percent women among students at our faculty. We are more lucky as a general university, because we have other faculties that make it more attractive for those multidisciplinary individuals. Technical universities have a bit of a harder situation, and the numbers are much lower there. The Czech Republic, according to Eurostat, has the lowest representation of women in the tech industry, at only ten percent among professionals. So I’m quite happy to see around twenty percent women in the classes at our faculty.

Matej Hrušovský: Where do you think the trend is going? Will it get to 50-50 representation?

Barbora Buhnová: That’s a very good question. I would say that the skillset needs we have in IT are changing. The ratio will depend on our ability to give credence to non-stereotypical skillsets, and that’s a huge problem we have at the moment. For example, a UX designer who is not interested in programming has a skillset that is assigned a lower value. It’s like we have this skillset that is a first-class citizen and then the skillsets that are second-class citizens.

“Diversity is not about boys and girls. It’s not about women and men.

Diversity is about being able to see value in different mindsets and problem-solving

strategies, and seeing value in people who are different…”

Until we learn to value both of these skillsets because they are both important for the industry overall, people who don’t have those stereotypical computing skills will leave the industry or hesitate to come in. If we learn to value all the skillsets we actually need in this industry, we can get very close to 50-50, but it may be a very long journey to rethink our notion of meritocracy.

Then there are many critics saying, “Look in those societies where they are very developed and women are free to choose anything. They still don’t choose computing.” And I ask them, “Why do you think they don’t choose computing? Because they don’t feel valued in computing.” People will choose a field that values what they bring to the table.

I don’t think reaching a 50-50 ratio is important. But when you have lower than thirty percent representation of a certain minority group, many people in that group will decide not to go into that industry. Some will avoid that course of study because they don’t feel they belong there. After you cross this threshold, people are choosing more freely.

To bring that back to the low percentage of women represented in tech in Czech Republic: I believe the industry is doing its best to change the message. The leaders of tech companies are trying. There is nobody putting up obstacles and saying, “You are a woman, you don’t belong here.” Still, many women do not go to the industry because they see that, right now, it is dominated by men, and they think, “I don’t belong there.”

Matej Hrušovský: Thank you for sharing your experience and knowledge on this topic. Is there anything else you think needs to be said?

Barbora Buhnová: In the end, it is about telling people who want to give tech a try to give it a try. If they need help, provide that help. Have more compassion for newcomers, because often girls take on the role of a newcomer. Whether it’s in elementary school or at a university, boys often have a longer history with computers than girls have. And it’s always difficult to be a newcomer.

Part of having compassion for newcomers is not trying to test them. Many people have a mindset like, “Okay, let’s give her this question to see if she is really good.” That’s a toxic mindset many people in IT have towards those who are different. And so many girls say they are getting tired of proving everybody wrong.

Instead, let’s be grateful for anybody who wants to get into this industry and help us work together, because it’s a big task and we don’t have enough people. Let’s make room for anybody who wants to give it a try.

SHARE THIS ARTICLE

More like this

The name Luke Hinds is well known in the open source security community. During his time as Distinguished Engineer and Security Engineering Lead for the Office of the CTO Red Hat, he acted as a security advisor to multiple open source organizations, worked with MIT Lincoln Laboratory to build Keylime, and created Sigstore, a wildly […]

“How many lives am I impacting?” That’s the question that set Akash Srivastava, Founding Manager of the Red Hat AI Innovation Team, on a path to developing the end-to-end open source LLM customization project known as InstructLab. A principal investigator (PI) at the MIT-IBM Watson AI Lab since 2019, Akash has a long professional history […]

John Goodhue has perspective. He was there at the birth of the internet and the development of the BBN Butterfly supercomputer, and now he’s a leader in one of the toughest challenges of the current age of technology—sustainable computing. Comparisons abound: one report says carbon emissions from cloud computing equal or exceed emissions from all […]

What if there were an open source web-based computing platform that not only accelerates the time it takes to share and analyze life-saving radiological data, but also allows for collaborative and novel research on this data, all hosted on a public cloud to democratize access? In 2018, Red Hat and Boston Children’s Hospital announced a […]

Everyone has an opinion on misinformation and AI these days, but few are as qualified to share it as computer vision expert and technology ethicist Walter Scheirer. Scheirer is the Dennis O. Doughty Collegiate Associate Professor of Computer Science and Engineering at the University of Notre Dame and a faculty affiliate of Notre Dame’s Technology […]

What is the role of the technologist when building the future? According to Boston University professor Jonathan Appavoo, “We must enable flight, not create bonds!” Professor Appavoo began his career as a Research Staff Member at IBM before returning to academia and winning the National Science Foundation’s CAREER award, the most prestigious NSF award for […]

Don’t tell engineering professor Miroslav Bureš that software testing can’t be exciting. As the System Testing IntelLigent Lab (STILL) lead at Czech Technical University in Prague (CTU), Bureš’s work bridges the gap between abstract mathematics and mission-critical healthcare and defense systems. His research focuses on system testing and test automation methods to give people new […]